Table of Contents

In Summary:

- The article explores ten unique African festivals, deeply rooted in spiritual beliefs, but often involving practices that appear unusual to outsiders.

- These celebrations range from vibrant public carnivals and courtship rituals to intense, private ceremonies involving spirit possession, animal sacrifice, and direct communion with ancestors.

- Many of the festivals exist at the intersection of tradition and modern controversy, sparking debates on issues like gender roles, animal rights, and cultural preservation.

- Each festival serves as a powerful mechanism for social cohesion, ancestral reverence, and the defiant celebration of life and identity within often challenging environmental or historical contexts.

Deep Dive!!

Thursday, 11 December 2025 – Africa's cultural landscape is a vibrant mosaic of traditions, where celebrations often transcend the ordinary to embody the profound, the sacred, and the strikingly unique. While the continent is renowned for its colorful and energetic festivals, some stand apart for their deep spiritual significance, complex historical roots, and practices that challenge outside perspectives. This article delves into ten of Africa's most extraordinary festivals, exploring the intricate narratives behind each one.

Moving beyond mere spectacle, these events serve as vital windows into the values, beliefs, and social structures of their communities. From a desert festival celebrating life against stark odds to a ceremony that redefines the relationship with death, each entry is examined through verified reports and anthropological insights. The following exploration is not a ranking of spectacle but a journey into the heart of cultural resilience, identity, and the powerful, sometimes paradoxical, ways human beings seek connection with each other, their history, and the cosmos.

10. The Cape Town Minstrel Carnival (Kaapse Klopse), South Africa

The Cape Town Minstrel Carnival is a symphony of satin, song, and social history that explodes through the city's streets every January 2nd. Known locally as Tweede Nuwe Jaar (Second New Year), its origins are a poignant tapestry woven from the pain of slavery and the resilience of joy. In the 19th century, enslaved people were granted only this single day of respite, which they claimed with defiant celebration, parading through the city. This tradition later absorbed influences from travelling American minstrel shows, leading to the vibrant costumes and painted faces seen today. For the Cape Coloured community, a group shaped by centuries of cultural fusion, the festival is a powerful reclamation of public space and a living, breathing archive of their complex identity, transforming memory into a deafening, joyful noise.

However, the carnival’s signature face paint, often white, and its"minstrel"moniker understandably spark modern controversy, evoking painful global histories of racist caricature. Scholars and community leaders, as noted in reports from institutions like the University of Cape Town, engage in ongoing dialogue about these symbols, emphasizing the festival’s evolution into a deeply localized expression separate from its American namesake. Today, it is less an imitation and more a robust, satirical commentary on politics and society, with troupes (klopse) spending the year composing sharp, witty songs. The controversy itself is part of its story, a vibrant, complicated annual debate about heritage, appropriation, and who gets to define the meaning of a community’s most public celebration.

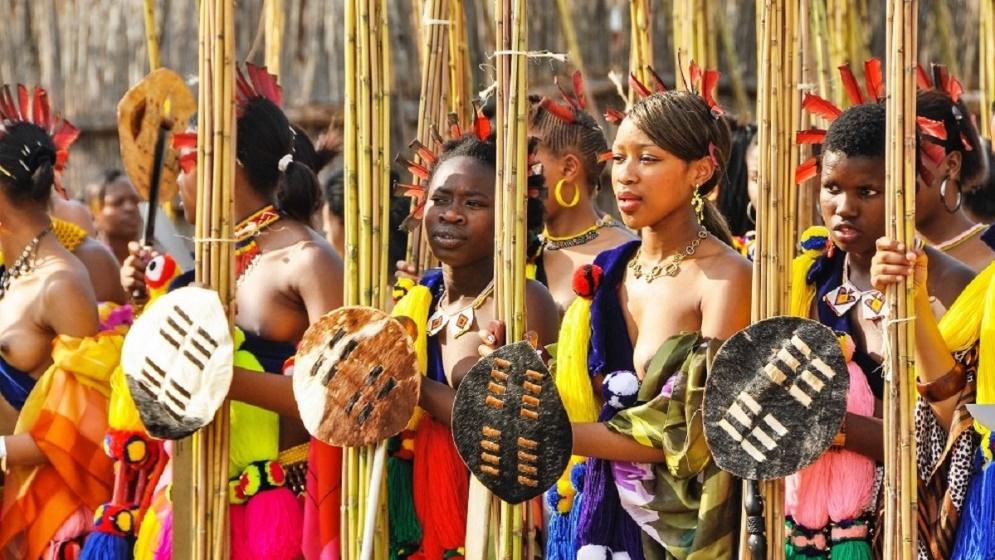

9. The Umhlanga (Reed Dance), Eswatini & South Africa

The Umhlanga, or Reed Dance, presents a breathtaking spectacle of unity and cultural pride, where up to 100,000 young women from across Eswatini and parts of South Africa gather in synchronized regiments, carrying tall reeds dressed in intricate beaded skirts and jewelry. As documented by the Eswatini Ministry of Tourism, the ceremony is a multi-day event that begins with the girls journeying to cut reeds, which are then used to repair the windbreak around the Queen Mother’s royal residence. The core ritual is a majestic, days-long dance before the royal family, a powerful display of discipline, song, and communal solidarity that reinforces national identity and celebrates the women’s role as carriers of culture and purity.

Yet, this dazzling display exists within a complex patriarchal framework that draws intense scrutiny. The festival’s emphasis on virginity testing and its context within a polygamous monarchy, where the king has historically chosen a bride from the participants, feels anachronistic to many human rights observers. Organizations like Amnesty International have criticized these aspects, while many participants and cultural custodians defend it as a voluntary source of pride and empowerment that resists Western judgment. This tension makes the Umhlanga a living paradox: a potent, visually stunning festival of female agency and community that simultaneously upholds traditional structures, forcing observers to grapple with the nuanced intersection of culture, autonomy, and evolving social values.

8. The Gerewol Festival, Niger

In the scorching Sahel, the nomadic Wodaabe Fula people stage one of the world’s most mesmerizing gender-role reversals: the Gerewol festival, a male beauty pageant where young men become the objects of scrutiny and desire. As chronicled by anthropologists like Angela Fisher and documented in UNESCO reports on intangible cultural heritage, participants spend hours meticulously applying elaborate makeup, using crushed minerals to create yellow foundations, kohl to elongate their eyes, and red ochre to highlight lips, and donning their finest beads and ostrich-plume headdresses. Their goal is to perform the precise, hypnotic Yaake dance, featuring exaggerated facial expressions, eye-rolling, and teeth-baring smiles, to showcase symmetry, health, character, and charm to the young women who act as judges.

This flamboyant spectacle is a profound cultural counterpoint. In a society governed by strict codes of reserve (pulaaku), the Gerewol provides a sanctioned, week-long space for overt pre-marital flirtation and competition. The festival, often held at the end of the rainy season when separate clans congregate, is a crucial mechanism for fostering social bonds and facilitating marriages outside immediate family groups. Far from mere theatre, it is a high-stakes ritual where aesthetics are directly tied to moral and genetic worth, ensuring the vitality of the tribe. In this breathtaking display, the Wodaabe articulate a unique nomadic ethos where beauty is a communal responsibility and a key to survival.

7. The Chewa Festival of the Dead (Kulamba Kubwereka), Malawi & Zambia

For the Chewa people, death is a transition, not an end, and the Kulamba Kubwereka ceremony is the vibrant, communal bridge that guides the recently deceased into the realm of the ancestors. As detailed in ethnographic research from the University of Malawi and Zambia’s National Heritage Commission, this annual gathering centers on the Kusinja Fumbi,the ritual"shaking off the dust."The bones of those who have passed in the preceding years are symbolically cleansed, allowing their spirits to fully integrate into the ancestral world and continue guiding the living community. It is a process of completion and welcome, turning grief into an act of familial duty and continuity.

The ceremony’s most visually striking element is the appearance of the Nyau secret society dancers. Clad in immense, full-body masks crafted from wood, straw, and cloth, they embody Gule Wamkulu,the"Great Dance", representing a vast array of spirits, animals, and satirical figures. As noted by UNESCO, which recognizes Gule Wamkulu as a masterpiece of intangible heritage, these performances are not for entertainment but powerful spiritual interventions. The masked figures, moving with often chaotic and intimidating energy, mediate between the living and the dead, enforcing social codes, and dramatizing cosmological truths. The festival thus transforms the cemetery into a dynamic stage for a profound dialogue with the afterlife, where fear, humor, and reverence intermingle.

6. The Ikoki (Palm Wine) Festival, Nigeria

In the lush, creek-lined communities of the Niger Delta’s Ijaw people, the Ikoki Festival is a sacrament of sacrifice where the community’ most valued liquid, palm wine, is offered back to the spiritual world in an act of extravagant libation. As recorded in studies from the University of Port Harcourt and Nigerian cultural archives, the festival is a prayer for prosperity, cleansing, and ancestral blessing. Participants engage in a marathon of drinking and, more significantly, pouring. Gallons of the frothy, fermented sap are deliberately spilled onto the earth, over shrines, and onto the bodies of celebrants. This "waste" is the heart of the ritual: a tangible offering that nourishes the gods and ancestors, ensuring they reciprocate with bountiful harvests, healthy children, and protection.

This lavish expenditure takes on profound symbolic weight in the context of the modern Niger Delta, a region paradoxically rich in oil resources yet marked by poverty and environmental degradation. The deliberate pouring of palm wine, a precious and labor-intensive resource, stands in stark contrast to the exploitation and pollution associated with the oil economy. Anthropologists interpret this, as per journals like Africa, as a powerful reassertion of traditional ecological and spiritual values. The festival becomes an act of faith-based economics, where community wealth is measured not in crude barrels but in shared sacrifice and the maintenance of a sacred covenant with the land and water spirits.

5. The Ounianga Festival, Chad

Set against one of the planet’s most surreal backdrops, the UNESCO-protected lakes of Ounianga in the Sahara Desert, this festival of the Toubou people is a defiant celebration of life in profound austerity. The strangeness is immediate and environmental: amidst a sea of orange, lifeless dunes lie a series of deep, permanent blue and green lakes, a geological miracle sustained by fossil water. Here, as documented by UNESCO and travel reports from agencies like Sahara Conservation, the Toubou gather for camel races, traditional songs, and dances that echo across the silence. The festival is a vibrant testament to human adaptation, where the community reaffirms its identity and deep knowledge of surviving in a landscape that appears, to outsiders, as inhospitable as Mars.

Central to the rituals are ceremonies of gratitude focused on water, the ultimate source of life. The Toubou, renowned as fearless desert nomads, perform specific dances and offerings to thank the spirits for preserving these rare oases. Ethnographic accounts note that the festival also serves as a crucial annual meeting point for scattered clans, functioning as a social, economic, and marital marketplace. In this context, the celebration is far more than a tourist curiosity; it is a vital mechanism for cultural preservation, ecological stewardship, and social cohesion, ensuring that the delicate balance between people and their precious, otherworldly home is maintained for another generation.

4. The Esoteric Festival of the Voodoo Covens, Benin

In the secluded sacred forests and compounds of Benin, the birthplace of Vodun, the most intense ceremonies are not public spectacles but private, esoteric gatherings of initiated covens. As reported by scholars in the Journal of Religion in Africa and documented by Benin’s own National Vodun Commission, these rituals are raw portals into a living animist worldview. Participants seek direct communion with the loas (spirits) through drumming, chanting, and animal sacrifice, typically chickens or goats, whose blood becomes an offering to bridge the spiritual and physical realms. The climax is often spirit possession, where initiates, in deep trance states, are believed to be mounted by a loa, their identity subsumed as they speak in altered voices, handle fire, or perform feats of startling strength.

This is the unvarnished core of a religion that shapes reality for millions, far removed from the sensationalized Hollywood caricatures. As noted in reports from the BBC and AFP, while Benin hosts a public National Vodun Day, the private coven ceremonies are where the religion’s profound theological and healing work occurs. Here, divinations are performed, conflicts are mediated, and illnesses, viewed as often spiritual in origin, are treated. For the devout, these gatherings are not "strange" but essential, a rigorous discipline and a direct line to the divine forces that govern health, fortune, and community order, offering a visceral, unfiltered glimpse into a complex and sophisticated spiritual system.

3. The Baboon Feast (Matshwa), Tanzania

In specific, isolated communities within Tanzania, the Matshwa ritual represents a profound and jarring intersection of traditional medicine, spiritual belief, and survival. As documented in anthropological studies, such as those cited in the Tanzania Journal of Health Research, this practice is undertaken as a last-resort curative for ailments or persistent misfortune diagnosed by traditional healers as stemming from witchcraft or spiritual attack. The ritual involves the hunting of a baboon, an animal whose intelligence and human-like qualities make it a potent symbolic counterpart. Its meat is then prepared and consumed according to strict ceremonial protocols, believed to transfer strength, confuse evil spirits, or break a malicious curse.

The practice, while rare and localized, is a stark example of sympathetic magic and highlights the enduring power of indigenous cosmologies in the face of unexplained suffering. Health researchers note that such rituals persist in areas where access to modern healthcare is limited and where traditional explanatory models for illness remain dominant. It underscores a worldview where health is a balance between the physical and spiritual realms, and where extreme remedies are justified by extreme afflictions. The Baboon Feast serves as a challenging reminder of the diverse, context-specific ways human communities confront fear, illness, and the unknown, operating within a logic that prioritizes spiritual resolution and communal healing.

2. The Umkhosi Wokweshwama (First Fruits Festival), South Africa

Revived under the late King Goodwill Zwelithini, the Zulu First Fruits Festival (Umkhosi Wokweshwama) is a potent, primal ceremony marking the new harvest and thanking the ancestors for renewal. At its most controversial center is a ritual where regiments of young Zulu warriors (amabutho) are tasked with barehandedly subduing and killing a bull. As reported by South African media outlets like the Mail & Guardian and cultural statements from the Zulu Royal Household, this act symbolizes the harnessing of natural strength, the channeling of collective warrior spirit, and an offering of the bull’s life force to the ancestral spirits to ensure national prosperity and unity. The consumption of the bull’s parts in a prescribed order completes this communion.

This ritual has placed the festival at the fiery crossroads of cultural preservation and global animal rights activism. Organizations like the SPCA and international animal welfare groups have repeatedly condemned the practice, leading to legal battles and intense public debate. Defenders, including cultural scholars cited by the University of KwaZulu-Natal, argue that the ritual is a sacred, centuries-old expression of Zulu identity and sovereignty, critiquing the imposition of Western ethical frameworks. The festival thus stands as a fiercely defended, deeply traditional spectacle that forces a direct and uncomfortable confrontation between the right to cultural practice and contemporary notions of animal welfare, with no easy resolution in sight.

1. The Famadihana (Turning of the Bones), Madagascar

The Famadihana of Madagascar’s Merina highlanders is arguably the continent’s most poignant celebration of the enduring family bond, one that literally bridges the gap between the living and the dead. As detailed by sources like the BBC and anthropological work from the Musée d’Ethnographie de Genève, every five to seven years, families undertake the joyful duty of rewrapping their ancestors. They open the family tomb, carefully lift the wrapped remains of their forebears, and cradle them in new, finely woven lambas (silken shrouds). To the exuberant sounds of live music, they dance with the bundles around the tomb, sharing news, introducing new family members, and pouring offerings of rum or perfume. The atmosphere is festive, filled with laughter, tears, and profound respect.

Far from being morbid, this ritual, as explained by local practitioners to travelers and researchers, is a sacred act of love, memory, and obligation. It is believed that until the body has completely decomposed, the spirit remains near the earthly realm. The Famadihana accelerates this process through the rewrapping, while also providing comfort to the spirit and reaffirming its place within the family lineage. For outsiders, the intimacy of handling ancestors’ remains is startling, but for the Merina, it is a beautiful and necessary rejection of permanent separation. It is a powerful, tactile philosophy that declares: our loved ones are not gone; they are simply waiting, and they are always welcome at the party.

We welcome your feedback. Kindly direct any comments or observations regarding this article to our Editor-in-Chief at [email protected], with a copy to [email protected].